Should we make an app?

Museums' perception of apps swung from silver bullet to waste of time - yet they can offer real engagement opportunities

| Estimated reading time: 14 minutes

It’s been 10 years since the launch of the iPhone and in that time museums and cultural organisations have been on quite a rollercoaster with this constantly evolving, yet now ubiquitous technology.

As smartphone ownership increased (now at 76% in the UK, while a February 2016 report from the Pew Research Centre states that a median of 68% of adults report owning a smartphone in 11 “advanced economies” countries) and mobile devices are taking over PC in accessing the internet, mobile is the way that many audiences mediate the world. However, it’s worth noting that the key change that came about in 2007 was the introduction of applications commonly known as apps - software that could be published by anyone and downloaded by users to their own device. Applications such as Word or Adobe PDF reader had been around for years but the idea that these were now easier to publish and easily accessible for people to download onto a device they carried with them all the time, seemed like the ultimate democratic product. Organisations could take control of their own digital destiny and so apps have come to dominate the conversation about mobile use.

We set up Frankly, Green + Webb in 2010 to help museums navigate the digital waters and in particular mobile. Our work takes us to the EU and USA where we use an approach that is both holistic and visitor-centred. This means we look at the whole visitor experience and identify if and how digital technologies may help rather than the other way around. I have worked with a diverse range of organisations from Tate to the Science Museum, English Heritage to Natural History Museum of Utah and Van Gogh Museum to Scottish Ballet.

The dominance of mobile means that the majority of museums have provided a minimum of an organisational website that changes what it looks like when viewed on a mobile device. They’ve also provided free wifi inside the museum. However, museums have also experimented and supported the use of smartphones and apps in many different ways.

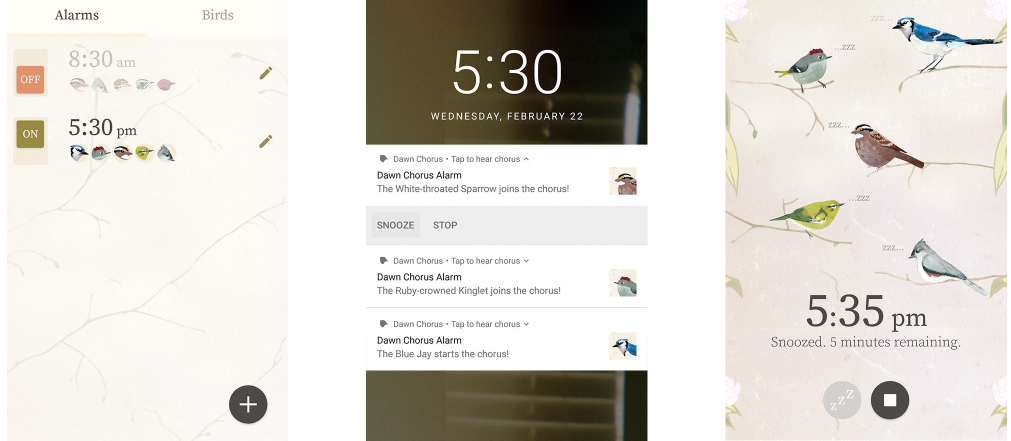

They have created bespoke apps and web apps as tools that promote the organisation’s work and their collection. For example, the Carnegie Museums of Pittsburgh’s ‘Dawn Chorus’ app (here for iOS and here for Android) uses the calls of birds that are studied by the museum as an alarm clock. Tate in the UK created ‘Magic Tate Ball’ (here for iOS and here for Android) that uses your location, the weather and ambient noise levels to recommend an artwork from their collection.

Other organisations such as the Lincoln Centre (here for iOS and here for Android) are using an app to provide services such as purchasing tickets, membership services and to find out about the length of the queue at the toilets. Others such as National Museums Scotland and Science Museum used mobile web apps (specially designed online experiences that you don’t need to download) to create games.

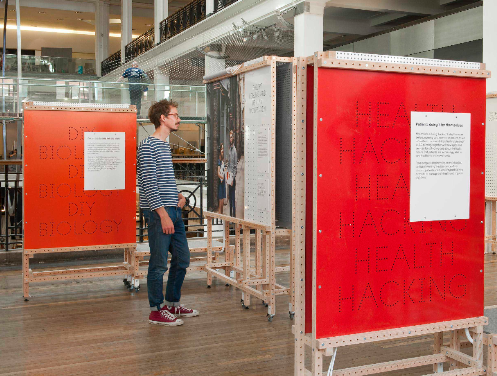

What I want to explore here is the area where the majority of organisations have invested, where the most challenges are experienced and where we’re beginning to see the most backlash – using mobile as a tool to augment the physical experience. Though our work concentrates on museums, most of the points I will be making in this article can be applied to any public-receiving organisation with a content delivery mission.

Museums' perception of apps swung from silver bullet to waste of time - yet they can offer real engagement opportunities

In the first few years, mobile – and apps in particular - were seen as the silver bullet to reach new audiences and give them access to the wealth of knowledge that museums own. There was a perception that users’ own devices would offer not only a richer experience but cheaper, simpler ways to deliver interpretation than more traditional approaches such as audio or multimedia guides – museums would no longer have to staff services or maintain equipment. Many organisations started to publish apps but the levels of use can be at best described as underwhelming. In addition, apps also proved more challenging to deliver and maintain than planned and therefore more costly. And so, almost inevitably, the pendulum has swung the other way and museums have pointed to overwhelming evidence that apps (and therefore mobile more generally) isn’t working for them and when asked if museums should invest in mobile the universal answer is “No”.

In our work we both research visitors’ attitudes to mobile; and evaluate mobile experiences – which means we see the rollercoaster from both the museum and the audience perspective and experience. The insights we’ve gathered show that audiences are very aware of the barriers to using mobile technology as part of a visit, and they have expectations based on preconceptions or previous experiences. However, when we talk to those who have used these experiences the majority report a positive impact – they feel they have learned more, had a better than expected experience and have looked at and explored things they wouldn’t have normally paid attention too. They also report feeling that the museum is more welcoming. Interestingly these results are similar no matter the device: a wand, a screen-based device or an app on their own device. In short, audiences appreciate well-designed mobile experiences no matter what the technology. However, they need support and reassurance to engage with this technology.

This suggests that visitors are open to the use of mobile technologies and where designed appropriately they can improve their experience. It also suggests that in the sectors’ haste to pigeon hole mobile either as a silver bullet or a complete waste of time, there is a chance of missing the opportunity altogether.

To reflect on the current app aversion, if we were to use the analogy of a museum exhibit it’s as if museums had decided that an exhibit is poorly received because all exhibits are bad, rather than the museum produced an exhibit that is neither compelling nor well designed and implemented. Yet, this doesn’t happen – partly because organisations are set up precisely to design and deliver exhibits: they recruit teams that are experienced in creating exhibitions for which they have adapted and refined their processes to ensure they deliver. They own the principles and affordances of the tools they are using to deliver knowledge and understanding. Mobile requires a similar approach and we need to be clear on what is needed to make these experiences successful.

Our research has highlighted some key principles that can help organisations choose if mobile experiences are right for their project and, if they do choose to implement, some key elements that are required to ensure mobile is used and enjoyed to the full.

Mobile experiences are invisible and intangible. This creates multiple barriers to audiences accessing, using and enjoying mobile experiences in museums. Different audiences, varying technology and the unique context of each museum mean that these barriers are raised and lowered dependent on the situation. The motivation of both organisation and audience to address these barriers is about effort versus value.

Value to the organisation

For organisations the question to always keep in mind is: “is this mobile offer important enough for me to dedicate time and money to addressing the audiences’ barriers to using it?” This may seem like an obvious point – but if what you are trying to do isn’t of strategic value to your organisation you shouldn’t be trying it. However, with new technologies it’s often the case where an organisation will be funded to develop something for its “innovative-ness” rather than its strategic value.

Failing apps: the majority lack internal support

The biggest challenge for most mobile experiences is that they are seen as an optional add on. This means that when internal budget and time is short they are often left to flounder. The majority of failing mobile experiences we’ve seen are due to lack of internal support. Mobile could be a strategy to improve a particular target audience’s visitor experience such as reducing queues, deepening engagement by delivering on one or two key learning objectives or encouraging first time audiences to return.

Value to the visitors

For visitors the question is: “is this experience compelling or does it meet my needs enough to take the time and energy to overcome the barriers to access it?” The challenge lies in that different audiences arrive with different needs. Who a person visits with, their understanding of the subject matter and whether they’ve been before are amongst the elements that are likely to affect the scale and type of needs they will have during their visit.

As in most instances mobile technologies are an expensive investment, it’s understandable that you want to make sure everyone uses it. However, in reality, this could mean that no-one uses them. If your organisation is looking to be more resilient by increasing the return rate of local audiences, try and understand why the local audience isn’t attending and what would make them come back for repeat visits. If international visitors are frustrated because they can’t find objects that are most important and relevant to them then try to understand where this moment of frustration happens and what is important to them. For example, a first time audience may feel they need to see the top 10 objects but they only have an hour or an expert audience may feel they want to have access to deeper information and carry out their own research.

Communicate who your app is for explicitly and why

Make sure you communicate who your app is for explicitly and why. Design it to be compelling and valuable enough to audiences to get them to invest the time, effort and/or money to download and use.

This commitment, created by a more strategic approach, then allows organisations to begin to address the operational barriers to audiences using mobile experiences - a challenge that requires the involvement of several departments across the organisation. In the following two examples, museum teams started with an understanding of their audiences’ needs. This has allowed the whole organisation to get behind the projects and the result is some of the highest take ups for apps we’ve seen and delighted visitors.

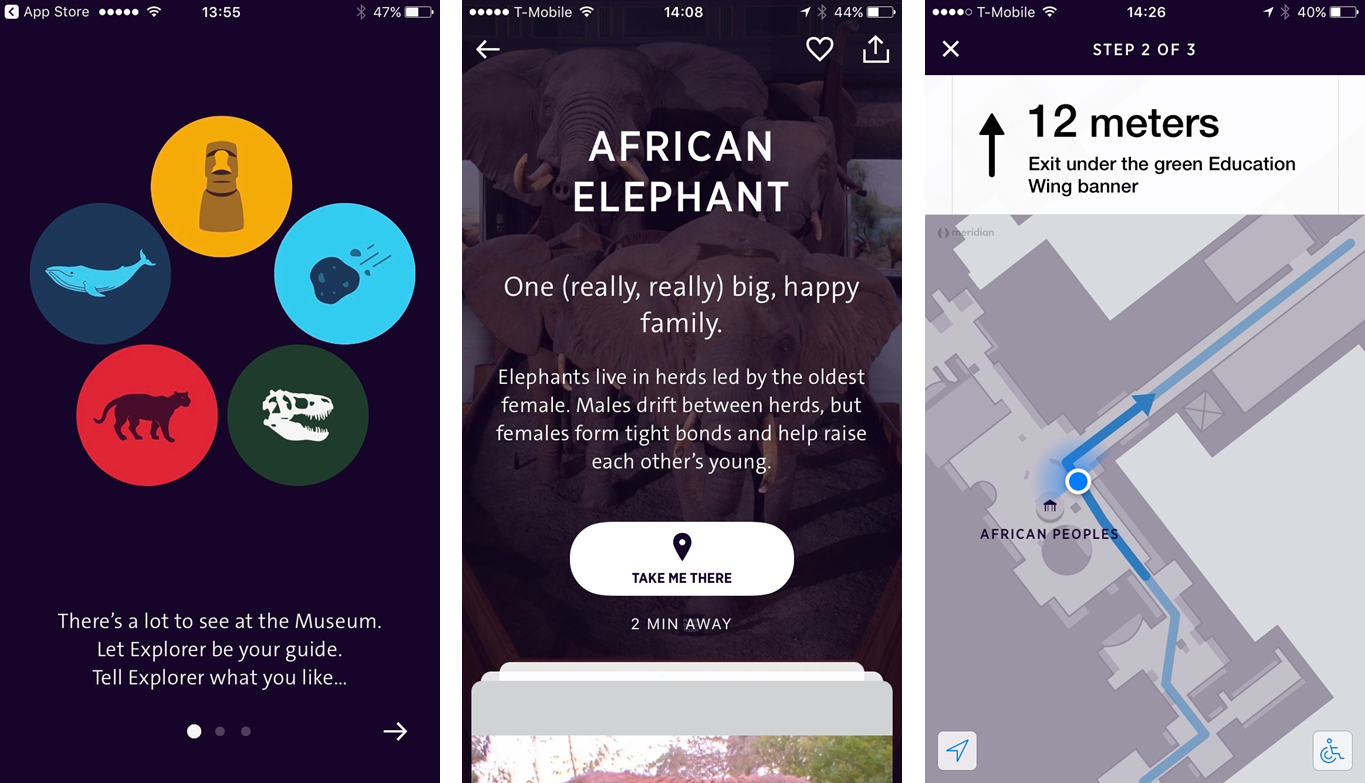

The American Museum of Natural History in New York, for example, identified that the main issue for visitors was that the Museum is vast and sometimes overwhelming - visitors couldn’t find the things that they had heard about. The Museum’s team were keen that they didn’t miss out on other interesting objects. The ‘Explorer’ app was designed to deliver turn-by-turn directions to help you see what you want to whilst highlighting elements along the way you might otherwise have missed. It also provides shortcuts to bathrooms, cafes and other important services. Visitors are highly motivated to solve that problem and so is the Museum.

The San Francisco Museum of Modern Art on the other hand wanted to deliver a programme that would encourage local visitors to keep returning and as a museum located in the Bay Area, close to the headquarters of many technology startups and multinationals, they created an experience that embodies that area. The experience combines indoor positioning with 15–45 minute immersive walks featuring a range of hosts including a documentary filmmaker, the host from the popular 99% Invisible podcast, and comedians from HBO’s Silicon Valley. Devices can be synced to allow this more social audience to listen with friends.

Making audiences aware

Not surprisingly, our research shows a direct correlation between awareness and use. Many people in museums feel mobile is the perfect solution to providing visitors with access to information without cluttering up the space with lots of signs. Unfortunately, mobile experiences with little signage, no hardware and no staff promoting them are, by definition, invisible.

Getting your target audience to use a service means doing a really good job of raising awareness that it exists. Make sure, no matter where people come from, that there are at least 5 points in the visitor journey where you have made them aware the service is available, before they have to make a decision about using the mobile experience. Chances are they will miss three and then see at least two.

You can do this using posters, online, in a queue, at the entrance, in the space where that app will be used. But the best way to promote a mobile experience is through staff.

Train your staff to spot your app's target audience

Train the information desk staff, visitor experience teams and security so they can spot your target audience, understand how the service will help them and recommend the app to them. If you can’t commit to raising awareness in this way, don’t be surprised if very few people use your mobile experience.

Promoting the experience at the right moment

The physical placing of promotional materials is also important: many mobile experiences are promoted on the edges of the gallery experience, however a lot of visitors only understand the value that a mobile experience may offer when faced with an indecipherable exhibit that makes them realise they need additional help.

Communicating the experience not the technology

When you raise awareness don’t just announce a mobile experience exists. Audiences are very aware of the practical barriers to accessing mobile services so they need to know that when they try, it will be worth the money and potentially the effort.

It’s important to explain who it is for and what it does to help them. Demonstrate the difference the mobile experience will have on their visit using video or other visitors describing the impact the mobile experience made to their visit.

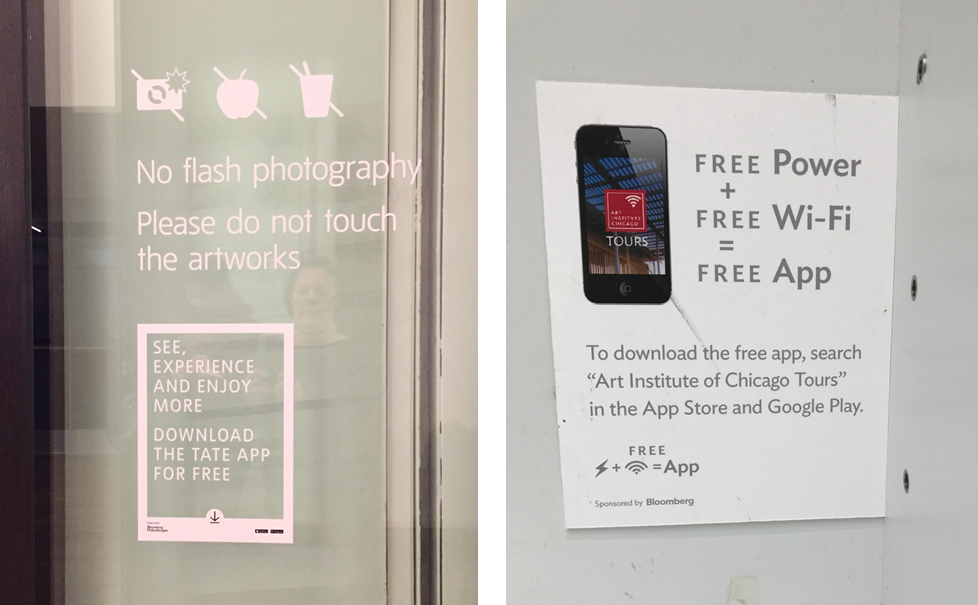

You will need to address their very practical and important barriers. “I can’t remember my password for the app store” “It might take forever and I don’t have long” “Will I kill my battery?” “Will I have enough data?”, are all statements we hear regularly. Not only ensuring that you provide this important infrastructure but also communicating this is likely to improve usage.

Designing beyond the screen

Good user experience (UX) on screen is a basic standard for a mobile experience, but audiences also have the physical UX — the museum or historic site — to deal with. Audiences regularly struggle to relate what they see on the screen to the physical environment or find that the design/content distracts rather than enhances an experience. This is particularly true the more interactive or multi-sensory the experience.

If you are doing anything more than providing text in front of an object, you should be thinking carefully about how you get someone started (this is called on-boarding in UX terms and there is la lot of info out there on it). All too often this ends up as a video with complex and lengthy instructions that audiences typically skip.

Good on-boarding: built into the experience

Good on-boarding should be built into the experience. And great on-boarding takes excellent UX design skills, testing (with users and in the space it’s designed for) and time.

So, should you have an app?

The fact that mobile technologies are so ubiquitous and are able to improve the experience for visitors means they should be part of the toolbox museums draw upon to support their visitors. Their success should be evaluated not in such binary terms as good or bad but, as with any tool, whether it’s the right tool, used in the right way and able to deliver the desired impact.

If we continue to evaluate digital technologies, and in particular mobile in such reductive ways there is a danger that we not only waste money, time and energy but we see technologies are written off before we have thoroughly explored their potential.

Many organisations are frustrated because they don't have the budget or team to implement such big programmes. Yet, these aren’t case studies in the technology as much as case studies in the strategic thinking and designing for audiences. Neither of which cost money, but they do take time and commitment. If the benefit of the mobile experience doesn’t feel worth this approach then the answer is definitely, no.